Mar 17, 2023

Term rewriting is one of the most fundamental techniques in programming languages. It is used to define program semantics, to optimize programs, and to check program equivalences. An issue with using term rewriting to optimize program is that, in a non-confluent term rewriting system, it is usually not clear which rule should be applied first, among all the possible rules. Equality saturation (EqSat) is a variant of term rewriting that mitigates this so-called Phase-Ordering Problem. In EqSat, all the rules are applied at the same time, and the resulting program space is stored compactly in a data structure called E-graph1.

EqSat has been shown to be very successful for program optimizations and program equivalence checking, even when the given set of rewrite rules are not terminating or even when the theory is not decidable in general. However, despite its success in practice, there are no formal guarantees about EqSat: for example, when does EqSat terminate, and if it does not, how does one make it terminate. The first problem is known in the term rewriting literature as the termination problem, and the second is known as the completion problem. Both problems are very hard, and there are a ton of literatures on both problems. In the setting of EqSat, these problems are not only theoretically interesting, but also have practical implications. For example, in program optimization, we may want to get the most “optimized” term with regard to a given set of rules, so making sure EqSat terminate is important to such optimality guarantees. Or, some theories are decidable but deciding them is slow, so one may want to speed up the reasoning by using EqSat, but there is no point in “speeding up” the decision procedure if it simply does not terminate. In this post, we will focus on the termination problem of EqSat. We don’t attempt to solve this problem entirely, but rather have this blog post as a first step and to draw community’s attention to this problem. In fact, we found many interesting results about this termination problem.

This post will show (1) how the innocent-looking associativity rule can cause non-termination, (2) why a terminating, and even canonical, term rewriting system does not necessarily terminate in EqSat, (3) how to fix the above problem by “weakening” EqSat’s merge operation, and (4) two potentially promising approaches to ensure the termination of EqSat. One fascinating thing I found during this journey is that, researchers working on tree automata indeed developed a technique almost identical to EqSat, known as Tree Automata (TA) completion. Different from EqSat, TA completion does not have the problem in (2) and is exactly the algorithm we will show in (3). Moreover, there is a beautiful connection between EqSat and TA completion: TA completion is the “preorder” version of EqSat.

Before understanding why associativity can cause non-termination, let us first briefly review some relevant backgrounds on ground theories and congruence closure.

A ground equational theory is an equational theory induced by a finite set of ground identities of the form \(s\approx t\), where both \(s\) and \(t\) are ground terms (i.e., no variables). For example, below is an example of a ground theory over signature \(\Sigma={a,b,c,f,g}\): \[\begin{align*} a&\approx f(b)\\ b&\approx g(c)\\ f(g(c))&\approx f(a)\\ \end{align*}\] All the equations that can be deduced from these three identities hold in this equational theory. For example, we have \(a\approx f(a)\) because \(a\approx f(b)\approx f(g(c))\approx f(a)\). Here, \(f(b)\approx f(g(c))\) is implied by \(b\approx g(c)\). In equational theory, a function by definition maps equivalent inputs to equivalent outputs.

A classic result in term rewriting is that the word problem of ground equational theory is decidable. A word problem asks whether two ground terms \(s\) and \(t\) are equivalent in a given theory. In general, this problem is undecidable. However, if the theory is ground, several algorithms exist that decide its word problem. One of the most well-known algorithm is the \(O(n \log n)\) congruence closure algorithm of Downey, Sethi, and Tarjan. One way to view it is that the congruence closure algorithm produces a canonical term rewriting system for each input set of ground identities: For theory \(E\), it builds an E-graph of the theory. Every E-graph corresponds to a canonical term rewriting system, which gives a way to decide \(E\). For example, the congruence closure algorithm will produce the following E-graph for the theory above: \[\begin{align*} c_a&=\{a, f(c_a), f(c_b)\}\\ c_b&=\{b, g(c_c)\}\\ c_c&=\{c\} \end{align*}\] where \(c_a, c_b, c_c\) denote E-classes of the E-graph, and \(a,b,c,f(c_a), f(c_b), g(c_c)\) denote E-nodes. This E-graph naturally gives the following canonical term rewriting system \(G\), which rewrite equivalent terms to the same e-class: \[\begin{align*} a&\rightarrow_G c_a\\ f(c_a)&\rightarrow_G c_a\\ f(c_b)&\rightarrow_G c_a\\ b&\rightarrow_G c_b\\ g(c_c)&\rightarrow_G c_b\\ c&\rightarrow_G c_c\\ \end{align*}\] Now, checking \(s\approx t\) can be simply done by checking if there exists some normal form \(u\) such that \(s\rightarrow^*_G u \leftarrow^*_Gt\) holds. For example, \(g(f(a))\approx g(f(g(c)))\) because \[\begin{align*} g(f(a))&\rightarrow_Gg(f(c_a))\\ &\rightarrow_Gg(c_a)\\ &\leftarrow_G g(f(c_b)) \\ &\leftarrow_Gg(f(g(c_c))\\ &\leftarrow_Gg(f(g(c)))) \end{align*}\]

This is sound and always terminates, because the term rewriting system produced by an E-graph is canonical—meaning every term will have exactly one normal form and term rewriting always terminates.

Associativity is a fundamental axiom to many algebraic structures like semigroups, monoids, and groups. It has the following form: \[x\cdot (y\cdot z)\approx (x\cdot y)\cdot z.\] This rule can be oriented as \(x\cdot (y\cdot z)\rightarrow (x\cdot y)\cdot z\) (or \(x\cdot (y\cdot z)\rightarrow (x\cdot y)\cdot z\)). It must be terminating, you may think, so we can just apply the associativity until saturation in EqSat, which will decide theories with associativity! Unfortunately, ground associative theories are not decidable in general. Term Rewriting and All That gives an example of undecidable associative theory (we write \(xy\) for \(x\cdot y\) and \(x\cdots x\) for \(x^n\) for brevity and associativity allows us to drop brackets): \[\begin{align*} (xy)z&\approx x(yz)\\ aba^2b^2&\approx b^2a^2ba\\ a^2bab^2a&\approx b^2a^3ba\\ aba^3b^2&\approx ab^2aba^2\\ b^3a^2b^2a^2ba&\approx b^3a^2b^2a^4\\ a^4b^2a^2ba&\approx b^2a^4 \end{align*}\] There is another way to state this proposition that appeals to math-minded folks: the word problem for finitely presented semigroups are not decidable.

Because of this, associative rules do not terminate in EqSat in general. Otherwise, given a set of ground identities \(E\), we can run the congruence closure algorithm over \(E\) to get an E-graph, and run EqSat with associativity rules. When it reaches the fixed point and terminates, this gives us a way to decide ground associative theories, which is a contradiction to the fact that such theories are not decidable.

To better understand why associativity does not terminate in EqSat, here is an example: suppose \(\cdot\) is associative and satisfy the ground identity \(0\cdot a\approx 0\) for constants \(0,a\). Now suppose we orient this identity into rewrite rule \(0\cdot a\rightarrow 0\) while having the associative rule \((x\cdot y)\cdot z\rightarrow x\cdot(y\cdot z)\). This is a terminating term-rewriting system (although not confluent, because the term \((0\cdot a)\cdot a\) has two normal forms \(0\) and \(0\cdot(a\cdot a)\)).

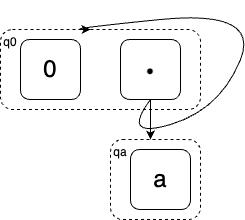

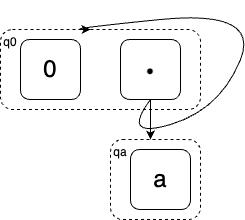

However, this ruleset causes problems in EqSat: Starting with the initial term \(0\cdot a\), EqSat will apply the rewrite rule \(0\cdot a\rightarrow 0\) and merge \(0\cdot a\) and \(0\) into the same E-class. The E-graph will look like this:

Notice that because of the existence of cycles in this E-graph, it represents not only the two terms \(0\) and \(0\cdot a\) but indeed an infinite set of terms. For example, \((0\cdot a)\cdot a\) is explicitly represented by E-class \(q_0\) because \[(0\cdot a)\cdot a\rightarrow^* (q_0\cdot q_a)\cdot q_a\rightarrow q_0\cdot q_a\rightarrow q_0.\] In fact, \(q_0\) represents the infinite set of terms \[0\cdot a\approx(0\cdot a)\cdot a\approx ((0\cdot a)\cdot a)\cdot a\approx\cdots.\] For any such term \((0\cdot a)\cdot\cdots\), it can be rewritten to a term of the form \(0\cdot (a\cdot \cdots)\). Now, for associativity to terminate, the output E-graph need to at least represent the set of terms \(a,a\cdot a,(a\cdot a)\cdot a,\cdots\), where any two terms are not equal. This requires infinitely many E-classes, each represents some \(a^n\), while a finite E-graph will have only a finite number of E-classes. Therefore, EqSat will not terminate in this case.

In our last example, the term rewriting system \(R=\{0\cdot a\rightarrow 0,(x\cdot y)\cdot z\rightarrow x\cdot (y\cdot z)\}\) is terminating, but \(R\) is not confluent. Confluence means that every term will have at most one normal form, and associativity is usually not confluent. At first I thought maybe non-confluence is what causes EqSat to not terminate. But this is not the case; there are canonical (i.e., terminating + confluent) TRSs that are non-terminating in EqSat. Here we give such an example: Let the TRS \(R\) be \[\begin{align*} h(f(x), y) &\rightarrow h(x, g(y))\\ h(x, g(y)) &\rightarrow h(x, y)\\ f(x) &\rightarrow x \end{align*}\]

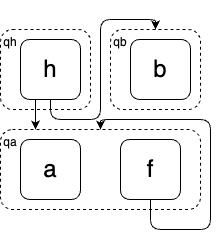

This is a terminating term rewriting system, where every term of the form \(h(f^n(a), g^m(b))\) will have the normal form \(h(a, b)\), no matter the order of rule application. However, this is not terminating in EqSat: consider the initial term \(h(f(a), b)\). Running the rule \(f(x)\rightarrow x\) over the initial E-graph will union \(f(a)\) and \(a\) together, creating an infinite (but regular) set of terms \(h(f^*(a), b)\). See figure.

Now, by rule \(h(f(x), y) \rightarrow h(x, g(y))\), each \(h(f^n(a), b)\) will be rewritten into \(h(a, g^n(b))\), so the output E-graph must contain \(g^n(b)\) for \(n\in \mathbb{N}\). But notice that the rule set will not rewrite any \(g^n(b)\) to \(g^m(b)\) for \(n\neq m\), which means that we have an infinite set of inequivalent terms \(b\not\approx g(b)\not\approx g^2(b)\not\approx \ldots\). Again, the existence of infinitely many e-classes, one for each \(g^n(b)\), implies that EqSat will not terminate.

For a terminating TRS, the set of reachable terms is always finite2. Intuitively, one will think that EqSat is just a more powerful way of doing term rewriting. So it is natural to think that running EqSat with a terminating TRS (with some initial term \(t\)) will eventually terminate. But this is not true, as has been shown in the last two sections. The issue is because EqSat is not exactly term rewriting: the equivalence in EqSat is bidirectional. For example, in our last example, the rewrite from \(f(a)\) to \(a\) does not only make the E-graph represent these two terms, but also \(f(f(a))\) and \(f(f(f(a)))\) and so on.

Before going further, let us first formally define the problem. For a TRS \(R\), we define the set of reachable terms \(R^*(s)=\{t\mid s\rightarrow_R^* t\}\). If \(R\) is terminating, \(R^*(s)\) is finite for any term \(s\). It can also be shown that EqSat always computes a superset of \(R^*(s)\). A natural idea is that if our EqSat procedure computes exactly \(R^*(s)\), it should terminate for terminating \(R\). And in fact it may also be capable of handling some non-terminating TRSs: E-graphs can represent many infinite sets of terms.

It turns out, term rewriting researchers have developed a technique that computes exactly \(R^*(s)\), represented as a tree automaton. The technique is known as tree automata completion, which is the main technique I hope to introduce in this blog post. TA completion proceeds as follows: build an initial tree automaton and run term rewriting over this tree automaton until saturation. Specifically, it searches for left-hand sides of rewrite rules, build and insert right-hand sides, and merge the left-hand sides with right-hand sides. Does this sound familiar? Yes, this is EqSat! It is striking that the program optimization and term rewriting communities independently come up with essentially the same technique.

But wait a second, didn’t we just say EqSat does not necessarily compute \(R^*(s)\) exactly? This is correct. There is a single tweak that distinguishes tree automata completion from EqSat. In tree automata completion, merging is performed directionally. For example, suppose the left-hand side is in E-class \(q_l\) and right-hand side in E-class \(q_r\), EqSat will basically rename every occurrence of \(q_l\) with \(q_r\) (or vice versa). As a result the two E-classes are not distinguishable after the merging. Tree automata completion, on the other hand, performs the merging by adding a new (\(\epsilon\)-)transition \(q_r\rightarrow q_l\) (remember the TRS view of an E-graph).

To better see the difference, consider the E-graph that represents terms \(\{f(a), g(b)\}\) \[\begin{align*} a&\rightarrow q_a\\ f(q_a)&\rightarrow q_f\\ b&\rightarrow q_b\\ g(q_b)&\rightarrow q_g \end{align*}\] and the rewrite rule \(R=\{a\rightarrow b\}\). EqSat will rename \(q_b\) with \(q_a\) (or \(q_b\) with \(q_a\)), so every E-node that points to child \(a\) (resp. \(b\)) now also points to \(b\) (resp. \(a\)). The E-graph after the merging will now contain \(\{f(a), f(b), g(a), g(b)\}\). Note that among these terms, \(g(a)\) is not reachable by \(R\); the rewrite rule \(a\rightarrow b\) can only rewrite \(f(a)\) to \(f(b)\), but not \(g(b)\) to \(g(a)\). In contrast, tree automata completion will add the transition \(q_b\rightarrow q_a\). Recall that we say a term \(t\) is represented by an E-class \(q\) in an E-graph \(G\) if \(t\rightarrow_G^* q\). With the new transition \(q_b\rightarrow q_a\), we have every term represented by \(q_a\) is now represented by \(q_b\), but not the other way around. As a consequence, \(f(b)\) is represented by the E-graph, since \[f(b)\rightarrow f(q_b)\rightarrow f(q_a)\rightarrow q_f,\] while \(g(a)\) is not represented.

This difference guarantees that TA completion will only contain terms that are reachable by the TRS. Moreover, if TA completion terminates, it will compute exactly \(R^*(s)\). The actual TA completion is slightly more general than this: instead of considering the set of reachable terms of a single initial term, it considers the set of reachable terms of an initial tree automaton, which may contain an infinite (but regular) set of terms. It turns out, although the set of reachable terms \(R^*(s)\) is always finite (and thus regular) for initial term if \(R\) is terminating, it is undecidable if the set of reachable terms is regular or not for an initial tree automaton even when \(R\) is terminating and confluent. To ensure the termination of TA completion even when the reachable set is not regular, researchers have proposed approximation algorithms for TA completion, which are useful for applications like program verification.

Equivalence and preorder. One interesting way of viewing TA completion is that it generalizes the equivalence relation in EqSat to a preorder: EqSat maintains an equivalence relation \(\approx\) between terms and asserts \(l\sigma \approx r\sigma\) for every left-hand side \(l\sigma\) and right-hand side \(r\sigma\). EqSat also guarantees that if \(t[a]\) is in the E-graph and \(a\approx b\), then \(t[b]\) is also in the E-graph and \(t[a]\approx t[b]\)3. TA completion, instead, maintains a preorder relation \(\lesssim\) and asserts \(l\sigma\lesssim r\sigma\) for every left-hand side \(l\sigma\) and right-hand side \(r\sigma\). \(l\sigma\lesssim r\sigma\) and \(l\sigma\gtrsim r\sigma\) in TA completion is equivalent to \(l\sigma \approx r\sigma\) in equality saturation, and in such cases \(l\sigma\) and \(r\sigma\) can be viewed as one state. Moreover, TA completion guarantees that if \(t[a]\) is in the tree automaton and \(a\lesssim b\), then \(t[b]\) is also in the tree automaton and \(t[a]\lesssim t[b]\).

Implementation of tree automata completion. I have not implemented TA completion, but it would be interesting to see how to implement TA completion in an EqSat framework like egg. It seems we only need to make two modifications: First, during rewrite, instead of merging left-hand side and right-hand side, add an edge from the left-hand side to the right-hand side (or equivalently, an \(\epsilon\)-transition from the right-hand side to the left-hand side). As an optimization, we can merge two states together if they are in the same strongly connected component. Second, modify the matching procedure so that it will also “follow” these \(\epsilon\)-transitions. The new matching procedure can no longer be expressed as a conjunctive query, as opposed to EqSat, and is more expensive to compute. In general, though, TA completion has a higher time complexity than equality saturation, since dealing with DAGs / SCCs are more difficult than dealing with equivalences.

The termination problem of tree automata completion. We have shown above that given a terminating TRS \(R\) and an initial term \(t\), tree automata completion is always terminating but EqSat may not terminate, which shows that the termination of tree automata completion does not imply the termination of EqSat. But is the other direction true? Indeed, the termination of EqSat does not imply the termination of tree automata completion as well! To see this, consider \[\begin{align*} f(x)&\rightarrow_R g(f(h(x)))\\ h(x)&\rightarrow_R b \end{align*}\] For tree automata completion to terminate, the set of reachable terms must be regular. However, for initial term \(f(a)\), the set of reachable terms is \[\{g^n(f(h^n(a)))\mid n\in \mathbb{N}\}\cup \{g^n(f(h^m(b)))\mid n>m\},\] which is not regular. In EqSat, because equivalence is bidirectional, all the \(h(x)\) are in the same E-class as \(b\), so the first rewrite rule can be effectively viewed as \(f(x)\rightarrow_R g(f(b))\), where the right-hand side is a ground term. As a result, there are only a finite number of equivalence classes in the theory defined by these rewrite rules, which implies the termination of equality saturation.

So far we have shown that TA completion is a variant of EqSat that is terminating for terminating TRS. But besides this we still have not shown anything positive about the termination of EqSat itself. In particular, although there have been research on when term rewriting terminates and when TA completion terminates, neither of them implies the termination of EqSat (and vice versa). My collaborators and I have been thinking about the termination problem for a while, and we have yet to come up with some non-trivial criteria4. Despite this, in practice there are many tricks people can use to stop EqSat early and still get relatively “complete” e-graphs. I will briefly mention two of them below.

Depth-bounded equality saturation. Let us define the depth of an E-class \(\mathit{depth}(c)\) to be the smallest depth possible among terms represented by the E-graph, namely \(\text{min}_{t\rightarrow^* c}\mathit{depth}(t)\). This is well-defined as we require all E-classes to represent some terms. Now, given a limit on depth \(N\), depth-bounded equality saturation maintains \(\mathit{depth}(c)\) for each E-class during equality saturation, and only apply a rewrite rule when any of the created E-classes does not have a depth greater than \(N\). Because there’s only finite number of E-graphs with bounded depth5, depth-bounded EqSat always terminates for any given \(N\).

There is something nice about depth-bounded EqSat. If two terms can be proved equivalent without using any term with depth \(>N\), depth-bounded EqSat can eventually show their equivalence. This is also useful in program optimization, where the optimal term is unlikely to be, say, 10\(\times\) larger than the original term. However, as I prototyped depth-bounded equality saturation a while ago, I found depth-bounded EqSat still took a very long time to terminate even for a reasonable \(N\). This somehow makes sense, since the number of trees with bounded depths grows rapidly.

Merge-only equality saturation. This idea has been around for a while and I think was first came up with by Remy. It is also very natural: We only apply the subset of rewrite rules if both the left-hand side and the right-hand side are already present in the E-graph. These rewrite rules essentially only merge E-classes together without creating any new E-nodes and are obviously terminating. They are useful when you have run EqSat for several iterations, want to stop there, but still want some relatively complete result. Merge-only EqSat provides the guarantee that if two terms can be proven equivalent using only terms in an E-graph \(G\), they can be proven equivalent by running merge-only EqSat over \(G\).

The reader should treat E-graphs and tree automata as two interchangeable terms. An E-graph is just a deterministic finite tree automaton with no \(\epsilon\) transitions and no unreachable states. Moreover, all tree automata in this post contain no unreachable states. ↩︎

This can be shown via König’s lemma for trees. Notice that TRSs are always finitely branching and rewriting in terminating TRSs will not contain cycles.↩︎

Relations with these properties are known as partial strong congruences.↩︎

There are some simple syntactic criteria that we can borrow from the ones for TA completion. For example, if all rules have right-hand sides with depth \(1\), equality saturation will always terminate because applying rules won’t create new E-classes. Similarly, if the right-hand sides are ground terms only, equality saturation will also terminate. The two criteria can be further combined: if the variables of the right-hand side terms only occur at depth \(1\), equality saturation will always terminate. ↩︎

Every distinct e-class contains (at least) one distinct term of depth \(N\). There are only finitely many depth-\(N\) terms, so finitely many E-classes. Finally, there are finitely many ways to connect finitely many E-classes.↩︎